In search of profits: world’s most intense competitive dynamics (Update June 16, 2025)

June 16, 2025

Note to readers: Sorry for missing an issue last Monday! A lot has happened in the world in the last couple of weeks.

It is a country with unprecedented market competition. Companies compete on price and cost intensely, and often race to the bottom until sustainable economic profits are non-existent.

What is competition? What does economics tell us about competitive dynamics in a perfect market?

If we take a step back to Economics 101, microeconomics theory teaches us a very simple dynamic:

If markets are perfectly behaved, as more suppliers enter to match demand:

Supply = Demand, and economic Profits = 0.

Let’s sell some hot dogs to understand why this is the case?

Imagine this scenario of hot dog stands in a baseball stadium.

Initially, you are the only hot dog stand (Only Hot Dog Stand) in the stadium, you charge $3 (price) for the hot dog.

Hot dogs sell like hot cakes, baseball fans love hotdogs. You sell 1,000 hotdogs each game, and it only costs you $0.50 (cost) per hot dog.

In a single game, you make $2,500 in profits (profits = 1,000 x ($3 - $0.50)). It’s an amazing business, there are almost 80 home games per baseball season.

That’s $200,000 in profits a year, for 1 baseball season that only runs ~50% of the year!

But after 1 season, an eagle-eyed shrewd season ticket holder Anne (with some capital at her disposal) realized your hot dog stand is very profitable.

Anne decides she’ll also open a hot dog stand (Anne’s Hot Dog Stand)! Anne’s Hot Dog Stand also charges $3 per hot dog.

The stadium’s fans are usually the same people, and a hot dog is a hot dog—there is no difference to fans. Fans end up splitting their purchases 50% / 50% between your Only Hot Dog Stand and Anne’s Hot Dog Stand.

Suddenly, your profits at Only Hot Dog Stand just tanked by 50%, you’ll only make $100,000 each year, instead of $200,000.

That is terrible news! So you ask around with the stadium’s fans. What would it take to get their business back?

The fans are motivated by their wallets, if Only Hot Dog Stand charges $2.90 instead of $3 per hot dog. All of their business will come back!

Okay, perfect, Only Hot Dog Stand lowers price to $2.9 per hot dog and recovers 100% of the stadium’s business. You lose about $8k/year of profits because of the lower price, instead of $100k/year. That seems like a great trade!

But terrible news, Anne also gets wind of this price change, and matches your price! Now, you’re back to splitting profits 50% / 50% at a lower price.

Long story short, if this cycle continues, Anne and your hot dog stand will race to set prices lower and lower, until you both make $0 profits.

You’ll price hot dogs as close to $0.50 until you both decide the stand is no longer worth the trouble. Now, no one gets a hot dog.

Case in point: China’s domestic EV market

In essence, this exact hot dog stand dynamic is happening across nearly all industrial markets in China.

Electronics, construction materials, apparel, plastics, car manufacturing, and logistics. In almost every single manufacturing and industrial sector in China, there is intense competition.

The competition is most apparent to consumers and foreigners in China’s domestic EV market. There are ~140 EV brands in China’s domestic market, and only ~20 are believed to be heading towards profitability by the end of 2030.

As of 2025, BYD is the world’s largest EV manufacturer, beating the innovative leaders like Tesla to surpass USD $100B annual revenue.

Recently, BYD decreased the price of their cheapest pure-EV model Seagull to ~$7,780 USD per vehicle. A new 4-door fully electric hatchback (with ~190 miles of range) for less than $8,000!

In April 2025, BYD sold about ~55,000 Seagulls in its domestic market in 1 month. By comparison, in the US and Canada, Tesla sold about ~45,000 vehicles in 1 month in the most recent quarter.

These price decreases triggered a new price war, similar to the hot dog stand price war. Impacting their profits, China’s EV stocks collectively fell amid news of more price discounts.

How do China’s massive car manufacturers pay for some of these price cuts? Unsurprisingly, they use the same tactics as massive US retailers (Walmart, Costco, etc..), they squeeze their suppliers.

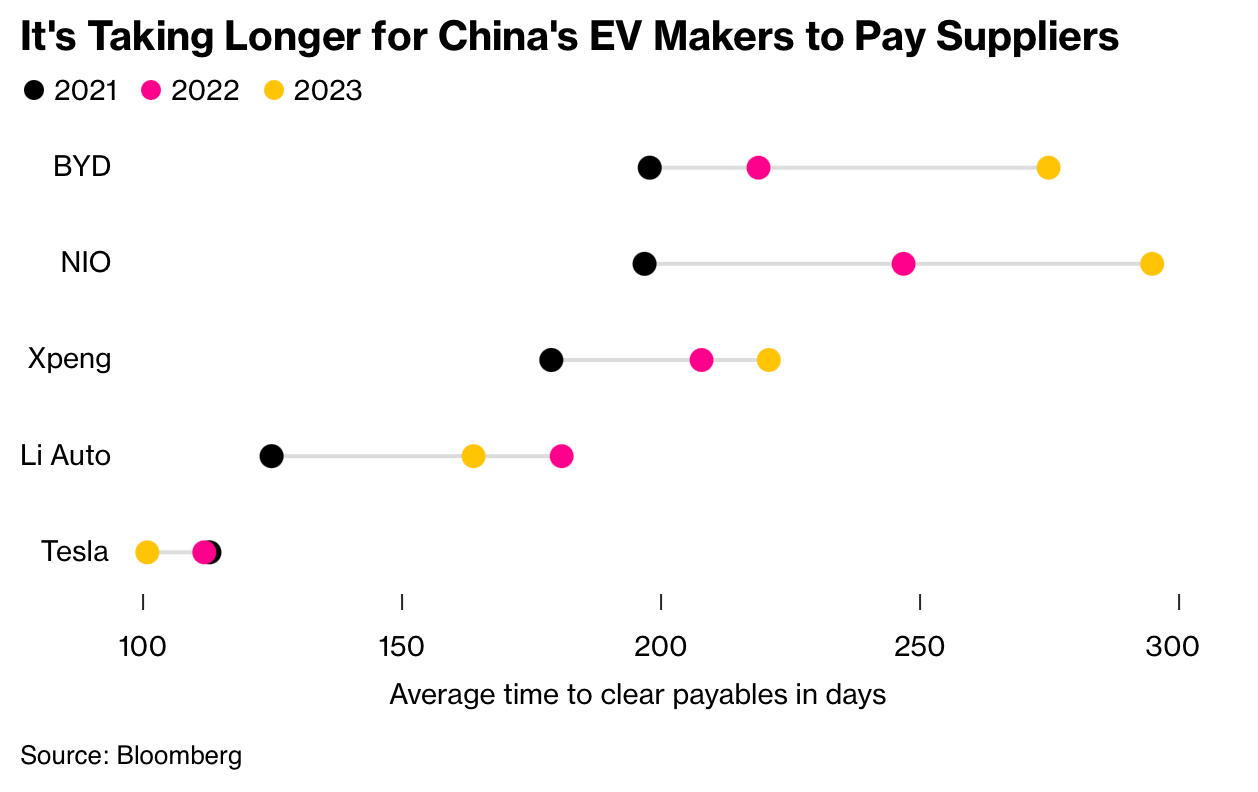

In 2023, BYD and NIO (another Chinese EV company) waited almost 260 days before paying their suppliers for delivered parts.

Imagine, if you had to wait 8 months before receiving your first paycheck after starting a new job!

China's central government was equally wary of this race to the bottom dynamic. Recently, it summoned the country’s top EV leaders, “urging” them to decrease payment terms. Soon after, Chinese EV makers individually publicly announced a return to 60-day payment terms.

In the case of China, there are no exits

In our hot dog stand case, the Only Hot Dog Stand and Anne’s Hot Dog Stand raced to a bottom price of $0.50 per hot dog. When the price war approaches the lowest price, it is very unlikely both hot dog stands will remain in business.

Anne and her shrewd business sense will likely decide to close up shop and not sell hot dogs for $0 profits.

However, in China, bankruptcies and business closings are much less frequent. Larger manufacturers, that were initially capitalized by loans from local city and provincial governments, very rarely close up shop.

Even when the company fails to generate profits, the plants continue to produce in order to keep workers employed. These zombie car plants are noticeably apparent, even to China’s central government.

Dayun, a China truck maker in inland China, is one of these zombie car companies. Its upstart in Shanxi (an inland rural part of China) uplifted the ancient city out of poverty and opportunity. Local governments bought ~33% of Dayun’s trucks in the 3 years before its IPO in 2020.

Without Dayun, Shanxi’s growth targets would be much more difficult to achieve. Its workers will go unemployed, and local politicians will be between a rock and a hard place (the people or the party).

Deflationary times ahead for China

China’s intense competitive dynamics is entirely deflationary. Competition drives prices down, and consumers experience lower prices.

Deflation can be just as harmful as inflation. Just ask Japan. The Bank of Japan tried for many, many years to stimulate spending with a negative interest rate. But people would rather lose money in the bank account than to spend it. They hope prices will keep decreasing, and it would be cheaper to spend in the future!

China’s cheap labor force provided an enormous deflationary force to the global economy since its entry into the WTO. Its current mature industrial capacity and prowess is always in search of profits.

When profits are swallowed up by new players, there are no more profits to be made. The cycle repeats.

Entering its 5th year of crisis, China’s property market was the first to fail in 2021. Its demise is in suspended animation due to government intervention. Opaque debt arrangements between China’s central bank, regional banks, local governments, and land developers prevent a total collapse of the market.

Book suggestion: Apple in China

If you’re looking for some summer reading, read Patrick McGee’s fantastic book on Apple in China. The electronics manufacturing prowess of China’s industries did not emerge from thin air.

Corporate investments by giants like U.S,’s Apple and Taiwan’s Hon Hai Precision (aka Foxconn) transformed the entire global electronics supply chain, starting with China’s manufacturing labor force and expertise.

See ya next week, enjoy the Summer Solstice on Friday.